As a hybrid one, you’re pushing through high training volumes. With each increase in volume, the risk of injury and overtraining rises. That’s why recovery is critical—more so than you might think.

In the past, I’ve suffered from several injuries and feelings of overtraining because I didn’t pay enough attention to recovery. Pushing your body through intense training is just half the equation. The other, equally important part, is recovery—it’s the key to keep progressing.

“Recovery is where the real results actually occurs.”

A common myth is that recovery means doing nothing, letting the body rest and heal on its own. What exercise science shows actually shows us that active recovery is far more effective than passive rest.

The good news is, there are practical tools and simple life changes that can help you recover faster, allowing your body to handle more load and improve performance. Recovery doesn’t need to be a time-and budget consuming process. With a few essential interventions (which I’ll share in this article), you can optimize your recovery and get the most out of your training.

Let’s dive in and see how you can accelerate your recovery and unlock your full potential.

This series has two parts:

-

- In the first, I break down recovery to its core, helping you grasp the fundamentals and how to measure it using tools like HRV and PRE.

-

- In the second, once you understand the basics, I provide practical tools and tactics you can start applying to your workouts and lifestyle right away.

Part 1

Before I explain what recovery really is, I want to tell you the core physiological principles. These will give you a deeper understanding and help you finally get what “recovery” is all about.

The Nervous system

This story starts with the nervous system.

Nerves are the wiring through which electrical impulses are sent to and received from all tissues of the body. The brain acts as “the central computer”, integrating incoming information, selecting an appropriate response, and then signaling the involved organs and tissues to take appropriate action. This allows for communication, coordination and interaction of the various systems in the body.

The nervous system is divided into two parts:

-

-

- Central nervous system (CNS): brain and spinal cord

- Peripheral nervous system (PNS): sensory & effector nerves

-

Sensory nerves inform the CNS what is going on within and outside the body.

Effector nerves send signals from the CNS to the various tissues organs and systems in response to the incoming information.

The efferent nervous system (effector nerves) is composed of two parts:

-

-

- Autonomic nervous system: involuntary control

- Somatic nervous system: voluntary control (movements): within our control

-

You might think: “What does this have to do with recovery?”

Well, let’s talk a about the “Autonomic nervous system”.

The ANS controls the body’s involuntary internal functions. Functions like heart rate, blood pressure, energy supply etc…

It has two major divisions which play an essential role in our evolution and survival:

-

-

- Sympathetic nervous system

This system is activated during a threat or crisis: it prepares the body for action by releasing stress hormones like epinephrine, norepinephrine, and cortisol. These hormones trigger key reactions: increased heart rate and cardiac contraction, enhanced blood flow to active muscles while reducing it in organs, higher blood pressure, and slowing down non-essential functions. In this state, the body is under stress, initiating catabolic processes that break down energy stores.

-

-

- Parasympathetic Nervous System: This system serves as the body’s “housekeeping” mode, focused on energy storage and recovery. It’s most active when the body is calm and at rest, driving anabolic processes that build and repair tissues, support digestion, and promote recovery.

Thanks to this energy management system, both humans and animals have survived. Survival depends on the ability to quickly generate massive amounts of energy (catabolic process) during moments of stress, and then replenish and conserve that energy during rest (anabolic process).

In an ideal world, the body would face stress, produce inflammation to address it, and then shut it off once the job is done, keeping everything in balance. The problem, however, is that we don’t live in a perfect world and we are continuously exposed to stress. The constant stimuli of our electronic devices, social media fighting to gain our attention, the constant work that never stops and the highly interconnectedness all lead to constant stress that takes it toll over time.

We need to learn how to “turn off” stress and become in a relaxing state by activating the parasympathetic nervous system.

A proven way to measure which nervous system is active is Heart Rate Variability (HRV). It tracks the time intervals between heartbeats. Unlike a perfectly steady beat, a healthy heart has slight variations in timing, driven by the balance between the 2 nervous systems.

-

- When the sympathetic nervous system is predominant, the HRV is low. We have a more regular and consistent heart rate because the body prepares for action.

-

- On the other hand, higher HRV indicates greater parasympathetic activity, showing the body’s adaptability and its ability to recover from stress.

Most smartwatches can measure HRV, and while not all are perfectly accurate, trusted devices like the Apple Watch provide fairly reliable data. Never interpret HRV in absolute terms and compare with others or ‘golden standard’. Each device uses a different method to calculate HRV. The key is to monitor your HRV trend over time and focus on your personal pattern. A consistent downtrend or significant decrease can indicate overtraining or insufficient recovery.

Although the processes of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system are completely involuntary, we can influence which system is active by various techniques:

-

- Breathing technique

-

- When you extend your exhalation, it activates the parasympathetic nervous system, particularly through the vagus nerve. This activation promotes a calming effect on the body, slowing down your heart rate and reducing stress.

-

- A longer inhalation tends to engage the sympathetic nervous system, which can increase alertness and slightly raise your heart rate.

-

- Healthy Habits Learn to managing stress by finding activities that you consider fun and are not related to a stress-related activity. Calm and quiet activities that make you feel relaxed can calm the mind and let go of the accumulated stress. Here arre some examples that works for me:

-

- Long walks in nature without phone

The role of recovery

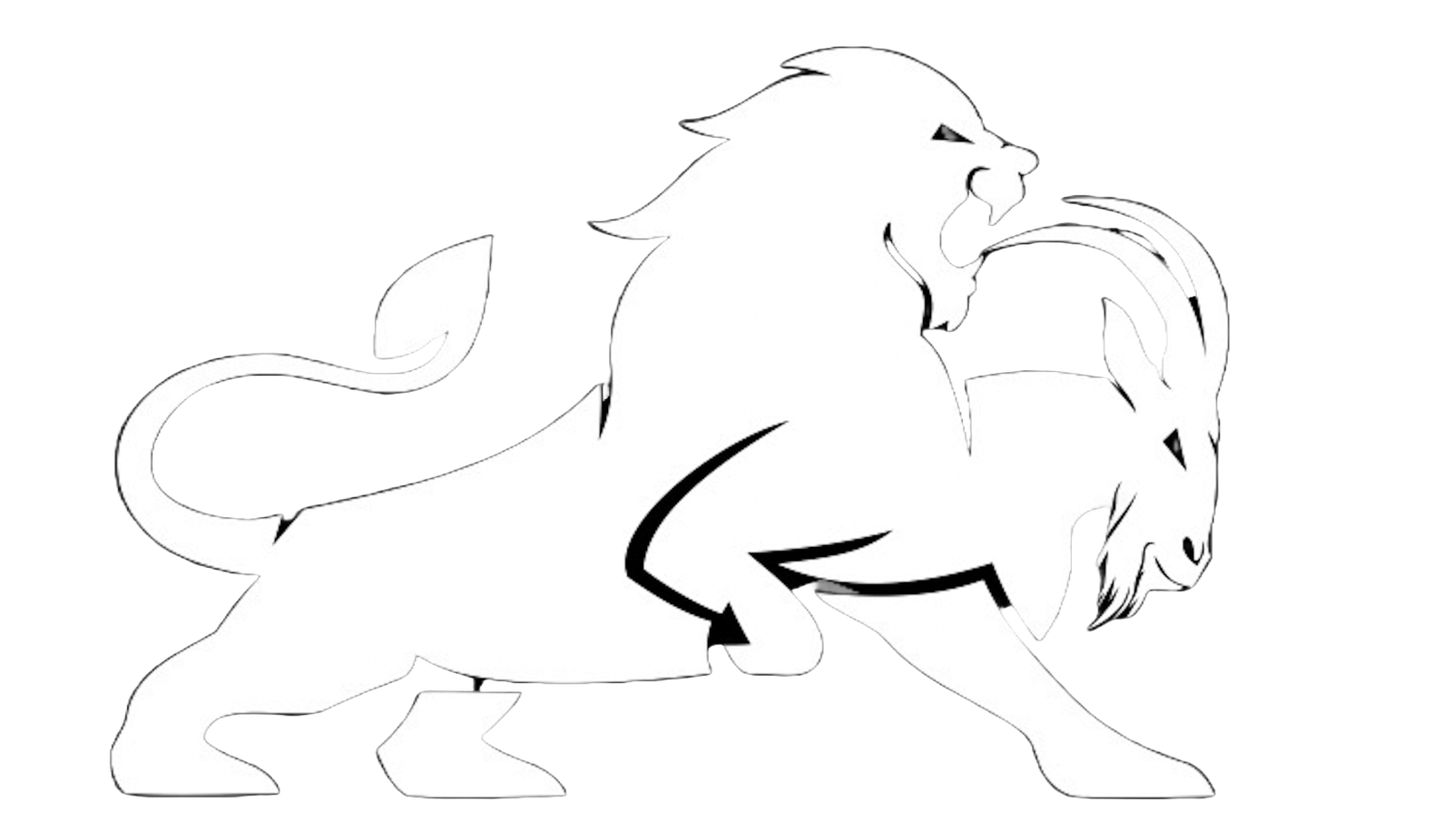

As explained in my post about the Hybrid Training Plan, our internal environment of the body strives to be in homeostasis (baseline). When we train, we put stress onto the body and disrupts the homeostasis (1) Our body will set in various mechanisms to recover from this disruption and try to get back to baseline, this is what we call recovery (2).

Here comes the magic: if we recover well enough and give the body enough time to do this, our body will not only go back to baseline will ‘level up’ to a higher level, so that the next time the same stressor is put onto the body, our body has become more adapted to this and can handle more of this stressor (3).

This process is called ‘hormesis’ in biology:

A low dose of a potentially harmful stressor can elicit a beneficial adaptive response. Too much of this is damaging or toxic.

Therefore, the higher the intensity of the training (stressor), the higher the increase in risk of ‘toxicity’ or in exercise language: ‘overtraining’

This brings me to the point I’m trying to make: we need to recover well enough.

What will happen if we don’t?

Let me introduce the 4 levels of recovery:

Level 1: Acute Overload (Recovery Time: Minutes to Days)

This is the immediate fatigue and drop in performance that occurs after each training session. It represents a typical training load where the body is stressed enough to improve both function and performance.

Level 2: Functional Overreaching (Golden Target) (Recovery Time: Few Days to a Week)

Functional overreaching involves brief periods of heavy overload without adequate recovery, thus exceeding the athlete’s adaptive capacity. There will be a brief performance decrement, from several days to several weeks, but when correctly periodizing and recovering well properly, performance will improve.

Level 3: Continue after point of functional overreached: non-functional overreaching (weeks)

This is when you don’t see an increase in performance after deloading and recovering from your overload. In the best scenario, you return to baseline levels after 3-4 days. N

Level 4: Overtraining (Recovery Time: Months)

refers to the point at which an athlete experiences physiological maladaptation and chronic performance decrements. Even after taking a month off, you may not feel better. This is rare but serious and professional help is needed.

The most important factor in recovery is giving your body enough time. However, we can also enhance recovery by using simple, time-efficient, and cost-free tools. Incorporating these into your routine helps maintain the hormetic balance, ensuring that the stress from exercise leads to positive adaptations rather than negative effects. (More on these tools and tactics in part 2.)

How to Assess ‘recovery’

Now that you’ve seen the different levels of recovery, it’s not always easy to know where you currently at.

Are you functionally overreaching and improving, or are you seeing a drop in performance, possibly indicating non-functional overreaching?

You can assess this by measuring different metrics:

This is mostly the first and most common sign that you’re probably overtraining.

Biomarkers

- Resting Heart Rate: An increased resting heart rate can indicate overtraining.

- Heart Rate Variability (HRV): A drop in HRV by about 20% suggests significant disruption.

- Blood Biomarkers:

This is the most accurate marker of all and tells a lot. Monitoring your blood markers quarterly or semiannually can help catch trends early.

-

-

- Elevated levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), which binds up testosterone.

-

- Changes in cortisol levels and stress-related biomarkers can indicate overtraining.

-

- Regular blood work to check cortisol and testosterone levels, especially their ratio, can give insights into overtraining.

-

-

-

Unintentional Decrease in bodyweight

-

Poor sleep quality

3. Psychological Markers

Non-specific symptoms like decreased motivation, adherence, appetite, and mood changes are classic signs of overtraining. Disturbances in sleep and a general lack of motivation to train are also common symptoms.

These tools can indicate when you’ve moved beyond functional overreaching, but how do you know if you’re non-functionally overreached (Level 3) or truly overtrained (Level 4)?

True overtraining is rare, and many people mistakenly think they’re overtrained when they’re actually just non-functionally overreached. The key difference is recovery time: if your performance returns to baseline within a few days to weeks, it’s likely non-functional overreaching. True overtraining requires much longer recovery, often months. If you suspect overtraining, it’s to get professional help.

It’s important to check in with these markers periodically, but don’t overdo it by tracking them after every session. Knowing your metrics can be both a blessing and a curse—a blessing to catch signs of overtraining, but a curse if you become obsessed with controlling every detail of your training and recovery.

Sometimes, push your limits and even exceed them. The human body is remarkably adaptable and can recover from a lot. Just be wise enough to recognize your breaking point and avoid pushing beyond it again. It’s normal to not feel 100% all the time—accept that. Trust your feelings and don’t rely solely on data. The goal is to build resilience, not become fragile.

How to prevent NFO/ overtraining?

Periodization: Managing Load with Volume and Intensity

Start by understanding your current load capacity: Are you new to running or lifting, or do you already have experience handling a regular training load without reaching non-functional overreaching (NFO) or overtraining? Like anything, too much can quickly turn negative.

Begin with your macrocycle, which is your plan for a 12-week period. The structure of this cycle depends on your goal—training for a marathon will require much more volume than preparing for a 5K, for example (This is what I mean by “arbitrary units” on the Y-as)

Next is the mesocycle, where the macrocycle is divided into three 4-week blocks. A common approach is the 3:1 ratio—where you gradually increase your volume and intensity by 5-10% over three weeks, followed by a deload week. During the deload, volume is reduced by 50%, allowing your body to recover and adapt to the previous training load (functional overreaching).

The final step is to periodize your week based on specific training sessions, called the microcycle. Here, we categorize workouts into three types:

-

-

- Peak Performance Day

This is when you push your body to its limits with the highest volume and intensity. No one can handle more than three of these intense sessions a week without risking overtraining.

For hybrid athletes, Peak Performance Days include:

-

- VO2 max Interval, Interval training

-

- Intense Lower body resistance training

When planning your week, start by deciding which days will be your Peak Performance Days. It’s crucial to follow these with lighter days—either an Activation Day or a Recovery Day (which I’ll explain soon). Avoid back-to-back Peak Performance Days. Limiting these to three per week will keep your training effective while reducing the risk of injury.

-

2. Maintenance Day

Unlike a Peak Performance Day, the purpose of a Maintenance Day is to provide just enough volume and intensity to maintain fitness and keep the body’s functions sharp.

Maintenance Days can include either high intensities with low volume or moderate intensities with moderate volume. In other words, these workouts are challenging but shouldn’t leave you completely exhausted by the end.

• Upper body resistance training • Zone 2 cardio

-

3. Recovery Day

If there’s one day that’s often overlooked, it’s the Recovery Day. The purpose is clear: speeding up recovery and allowing higher training volumes without the risk of overtraining. Unlike passive rest, active recovery is the focus here—light exercises, soft tissue work, or swimming, for example (A deeper dive in part 2)

Special Credits to Joel Jamieson for educating me on this topic.

Use the Perceived Rate of Exertion (PRE) to evaluate the intensity of your training. It is a score that you give to your effort and can give you an idea which of the three training day you underwent. You can look op the scores and ranges online. To give you some general guidelines:

-

- Recovery Days: Score: 1-3

-

- Maintenance Days: Score: 4-7

-

- Peak Performance Days: Score 8-10

How to take action when NFO/ overtrained

If you experience symptoms for just a day or two, don’t jump to conclusions about being overtrained. It’s normal to feel off occasionally. However, if symptoms persist for more than five days, it’s time to take them seriously and take action:

-

-

- Start with complete rest for the next few days.

-

- Immediately reduce your training volume.

-

- Monitor biomarkers and symptoms to track any changes.

-

- Focus on Nutrition: Make sure you’re eating enough calories and nutrient-dense foods to aid recovery. Overtraining is often linked to calorie deficits.

-

- Adjust Your Mindset: ****Reframe your approach from thinking in terms of “being overtrained” (a noun) to actions (verbs) and processes that contribute to recover.